Since March 2020, when the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, people around the world have been inundated with messages about how to prevent the spread of the deadly virus. For some, these messages stick. They heed the warnings of public health officials, washing their hands longer and more frequently and wearing a mask. But others hear these same messages as merely advice.

Americans have witnessed pandemics and epidemics in the recent past. The 2017-2018 influenza season, for example, was among the worst documented. The CDC reported nearly 45 million infections, more than 808,000 hospitalizations, and more than 60,000 deaths in the United States alone. Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, many people, including some public officials, have compared it to flu. Although this comparison may have been intended to help the public understand the risks and importance of hand hygiene as it relates to germ theory, it quickly became apparent that the public interpreted this comparison as a sign that this new viral threat was similar to flu in severity and impact. As the numbers of COVID-19 infections and resulting deaths increased, it became clear that this virus was not like flu. Taking steps to avoid viral transmission and infection became critical. But by August, as people grew weary of mitigation strategies, they eagerly anticipated a solution similar to seasonal flu; the public conversation turned to focus on vaccination.

In a contentious election year, politicians and public officials have, at times, disagreed on how to communicate about the necessity of wearing masks, the virus’s death toll, and how quickly a vaccine might be made available to the public, among other factors. The disagreement was aired to the public when the administration approved emergency use authorizations for treatments based on case studies rather than trials. Both hydroxychloroquine and convalescent plasma were touted as potential treatment options, despite inconclusive evidence of efficacy. Within this equivocal information environment, politicians and government officials released information and expectations that, at worst, conflicted with emerging science. Even among administration officials, two conflicting messages have been released: politicians have made promises of a COVID-19 vaccine as early as November, and public health officials have warned about the potential harm of releasing a vaccine without enough evidence of its safety and effectiveness.

Communication scholars and practitioners are uniquely situated to provide insight into the foundation of any successful communication campaign: credibility.

Teams around the world are developing and testing vaccine candidates, with some already reaching human trials. Yet, the successful development of a proven vaccine does not equate to a fully vaccinated public. The process of manufacturing and distributing a vaccination is a complex logistical challenge. And, even once a vaccine reaches clinicians, the greatest challenge to the patient is “the last three feet,” a phrase coined by Edward R. Murrow. Despite flu’s seasonal predictability, millions of dollars are spent each year on immunization marketing campaigns. The integrated marketing communication strategy for a COVID-19 vaccine will be critical, given the early debates about the vaccine. Communication scholars and practitioners are uniquely situated to provide insight into the foundation of any successful communication campaign: credibility.

Susan T. Fiske and Cydney Dupree have described credibility as a function of expertise and trust. Twenty years ago, physicians were viewed as credible because patients saw them as trustworthy and competent. Physicians also served as the primary communicators of health information. Today, however, as explained by World Health Organization Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, “We’re not just fighting an epidemic; we’re fighting an infodemic.” The availability of online information and the diffusion of social media have led to an epidemic of misinformation that transcends geographic borders and distances and spreads rapidly. Previously, people interacted with fewer sources of competing and conflicting health messages. Now, surrogate information providers communicate health information between medical appointments, or provide information as supplementary to physicians. Yet, while many of these information sources lack the expertise of physicians, they often have experience with a specific illness. In this information-rich environment, clear, consistent, credible messaging is key to public health.

Credibility as Trust, Expertise, and Experience

Healthcare providers are often cited as trusted or preferred information providers in vaccination decisions. And, to ensure vaccination, patients must comply with physician recommendations. However, it is common for patients and patients’ parents to seek medical information outside the physician’s office, receiving input from multiple channels and sources. In this instance, while the physician retains the role of expert, these sources are also often afforded credibility because of their experience rather than their education or credentials. In The Wisdom of Crowds, this phenomenon is referred to as a “smart” group by James Surowiecki. These “smart” groups are diverse and decentralized. They are capable of providing specific knowledge and observations, regardless of how individual that knowledge or experience may be. This is a deviation from the traditional understanding of credibility as a function of trust and expertise. Rather, experience may be a third dimension of credibility.

While expertise is often confounded with experience, these concepts are not equivalent. Rather, expertise can be either educated expertise or experiential expertise. For example, after years of academic and clinical rotations and simulation training, a new surgical resident has developed educated expertise. But on that resident’s first day, they have not experienced solo surgery; they do not yet have experiential expertise. Surgeons gain experiential expertise over time. In the context of surgical treatments, a breast cancer patient may accumulate experiential expertise as they live through the process of pre-op and surgical procedures and surgical recovery, but they are unlikely to complete the academic and clinical rotations or simulation training they would need to develop educated expertise. In health fields other than surgery, these two forms of expertise are harder to differentiate.

As a novel viral illness, COVID-19 requires the attention of many types of experts – virologists, epidemiologists, immunologists, pulmonologists, biological engineers, etc. Each of these traditional experts has educated expertise derived from their education and training, each has accumulated experiential expertise in their fields, and each are accumulating COVID-19-specific expertise in real time. Patients are also developing COVID-related expertise. Whereas scientists who study infectious disease have earned their expertise, we often afford expertise to individuals who have had an experience with COVID-19. Through social and news media, we see these patients share that experiential expertise with the public.

The government’s choice of COVID-19 spokespersons presents different tactics on communicating health messages. When the president determines who will speak at a White House Coronavirus Task Force meeting, he affords that speaker credibility simply by allowing them to address the nation about the illness. Dr. Anthony Fauci was a key figure in the first months of the task force, often appearing with the president during press briefings. Many Americans were familiar with Dr. Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), from his time as a spokesperson throughout the AIDS epidemic. He has both educated expertise and experiential expertise, as he has led NAIAD for more than 35 years, is one of the most cited researchers in history, and has developed effective therapies for once fatal inflammatory and immune-related diseases.

The government’s choice of COVID-19 spokespersons presents different tactics on communicating health messages. When the president determines who will speak at a White House Coronavirus Task Force meeting, he affords that speaker credibility simply by allowing them to address the nation about the illness. Dr. Anthony Fauci was a key figure in the first months of the task force, often appearing with the president during press briefings. Many Americans were familiar with Dr. Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), from his time as a spokesperson throughout the AIDS epidemic. He has both educated expertise and experiential expertise, as he has led NAIAD for more than 35 years, is one of the most cited researchers in history, and has developed effective therapies for once fatal inflammatory and immune-related diseases.

In August 2020, President Trump appointed a new advisor to the Task Force, Dr. Scott Atlas. Dr. Atlas is a neuroradiologist and senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, a Stanford University public policy think tank. He is neither an infectious disease expert nor an epidemiologist, and his lack of direct patient care led physician-turned-actor Ken Jeong to tweet, “I have more direct patient care than Scott Atlas…” Further, several of Atlas’s former Stanford University Medical School colleagues released a letter to call attention to Atlas’s "falsehoods and misrepresentations of science.” Indeed, Atlas’s messages about COVID-19 prevention and treatments clash with other task force members’ messages. However, because he is a physician, and because the president has promoted him as a leader on the Task Force, he is afforded expertise by members of the public who do not understand the difference between his expertise and experience and Dr. Fauci’s expertise and experience.

We all likely know of people who have earned their expertise, and others who were afforded expertise when they communicated their experience to others. This communication may come via interpersonal or mass media channels. Jenny McCarthy, a television personality, once claimed that vaccinations lead to autism. Because of her social media following and status, people listened to her for advice on autism and vaccinations. Her credibility was based on personal experience; she claimed her son had developed autism after receiving a measles vaccination.

Relayed experiences alter the way we think about the severity of the virus and our own susceptibility for contracting it.

Likewise, as the numbers of people infected with COVID-19 increase, we likely know someone who has had the virus, or have heard of someone who did. Whether first- or second-hand, these relayed experiences alter the way we think about the severity of the virus and our own susceptibility for contracting it. When a person explains that their experience with COVID-19 was mild, for example, it may reduce concern among individuals who trust that person’s experience.

These examples of conflicting information, or even miscommunication, further contribute to an infodemic, passing misinformation from person to person. When a non-expert public official contradicts public health experts about the likelihood of safe and effective vaccination availability, public opinion about vaccinations can be influenced. The way we receive information, and from whom we receive it, can impact whether we heed the advice from public health officials and our own physicians about whether to be vaccinated. When conflicting messages are present, people are forced to choose between expertise and experience. They must decide which is more important to them in decision-making—the person with educated, or earned, expertise or the person with experiential, or afforded, expertise.

This is where trust becomes even more important to the credibility formula. Trust trumps expertise and experience when conflicting information is presented. The challenge, of course, is that everyone’s trust level is different and based on their own field of experience. If a person respects education, they may be more likely to trust educated experts. If a person lacks access to quality healthcare, but has a strong social network, they may be more apt to trust the experience of a close friend or family member. There are those who believe healthcare providers have an agenda, such as promoting a specific vaccine, to receive financial kickbacks. It is also possible that these people do trust educated expertise, but that the messages are drowned out by louder and more active experiential experts or lesser qualified educated experts. Regardless, when making important health-related decisions, conflicting information will be evaluated based on which source is more trustworthy, and trustworthiness is a trait each person evaluates individually.

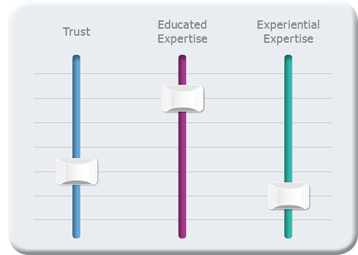

Ideally, a person speaking about COVID-19 would have all three traits discussed here: trustworthiness, expertise, and experience with COVID-19. Yet, that is rarely the case. Thus, these credibility traits can be thought of as a type of equalizer. Just as an audio equalizer allows the listener to control frequencies to achieve a better sound or to eliminate feedback or unwanted noise, audiences control message source inputs based on these three traits. Some will choose to listen to a source when they find that source to be trustworthy, even when the source’s educated expertise is low and their experiential expertise is moderate. For others, the most influential sources will be more trustworthy and have greater educated expertise, while having low experiential expertise. Each person is influenced differently by the presence of these traits.

Ideally, a person speaking about COVID-19 would have all three traits discussed here: trustworthiness, expertise, and experience with COVID-19. Yet, that is rarely the case. Thus, these credibility traits can be thought of as a type of equalizer. Just as an audio equalizer allows the listener to control frequencies to achieve a better sound or to eliminate feedback or unwanted noise, audiences control message source inputs based on these three traits. Some will choose to listen to a source when they find that source to be trustworthy, even when the source’s educated expertise is low and their experiential expertise is moderate. For others, the most influential sources will be more trustworthy and have greater educated expertise, while having low experiential expertise. Each person is influenced differently by the presence of these traits.

As Communication scholars and practitioners, we must continue to work together to plan public communication campaigns to disseminate COVID-related, evidence-based health information. We need to ensure the focus is on clear, consistent messages that are delivered by credible sources. To identify the most credible sources for our audience, we must first listen to our audience. We need to know which credibility trait is most important to them. As we segment audiences, we must work to match each audience to the source they perceive as most credible. For one audience, it may be Dr. Fauci, but for another it could be a local pastor or a social media influencer. As Communication scholars and practitioners, we can use our expertise and skills to improve provider-patient communication and communication within our communities. We can help healthcare providers better communicate about critical topics and prepare them for how to talk to a patient who is prioritizing advice from their social network over advice from their personal physician. We can also partner with our communities in community-based participatory research to build relationships that can help us better understand our audience and communicate more effectively, even in times of infodemics.

Disclaimer: The views expressed within this publication represent those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, or the U.S. Government, the Department of Defense at large.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

LAKESHA N. ANDERSON is Director of Academic and Professional Affairs at the National Communication Association and an instructor with Johns Hopkins University’s Communication MA Program, where she teaches course in health, risk, and crisis communication. Her mixed-methods research explores health risk messaging and women’s health communication with a specific interest in social support. Anderson earned her Ph.D. in 2010 from George Mason University in health and strategic communication.

CHRISTY J.W. LEDFORD is an Associate Professor in the Department of Family Medicine at Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. As a health communication scientist, she seeks to integrate Communication principles into medical education and practice, both through theory and the application of mixed methods research. Ledford’s research focuses on how patients and physicians can negotiate emerging evidence together. She taught public relations and organizational and interpersonal communication before transitioning to medical education in 2011.