Can We See from One Another’s Perspective Using Virtual Reality?

What if you could see the world from someone else’s perspective? What if technology could help you feel as if you were really there? With virtual reality (VR) technology, people may be able to experience others’ perspectives in a new way. In a new article published in NCA’s Review of Communication, Maud Ceuterick and Chris Ingraham examine the VR film, Traveling While Black, to explore how virtual reality (VR) can be used for immersive storytelling.

Virtual Reality

Ceuterick and Ingraham argue that virtual reality can help bridge the gap between our own perspective and those of others by “locating the viewer within a world that is not otherwise accessible to them, whether because it is nonlocal, imaginary, forbidden, or because it involves people whose different identities and communities—and hence whose stories, histories, and ways of being—are ordinarily beyond the purview of a viewer’s personal experience.” In other words, the sensation of being somewhere or someone else can transcend a boundary that words or films by themselves may not be able to cross.

Ceuterick and Ingraham argue that VR affords little opportunity to escape to the outside world, except by removing the VR headset. The goal of VR is to be immersed in the scene. This contrasts with traditional films in which the audience participates in the narrative by watching but still remains outside of the narrative itself. This separation, termed “the fourth wall,” can sometimes be broken in narratives, such as when a character directly addresses the audience. However, the audience is still separate from the characters and the film’s narrative.

Traveling While Black

Traveling While Black is an Emmy-nominated VR film that was released in 2018. In the film, the audience is brought into Ben’s Chili Bowl, a real-life Washington, D.C., restaurant. The restaurant has historically served as a haven for the Black community; it was even listed in the Negro Motorist Green Book, a mid-20th century travel guide for Black Americans. Ceuterick and Ingraham argue that Ben’s Chili Bowl is representative of safe spaces for Black Americans during the Jim Crow era and of the travails that Black Americans faced when traveling, such as the threat of police violence. In Traveling While Black, the characters present stories about how their agency and freedom to travel safely has been denied in the United States. The film moves through time from the 1950s to the present and addresses pressing issues, including Black Lives Matter.

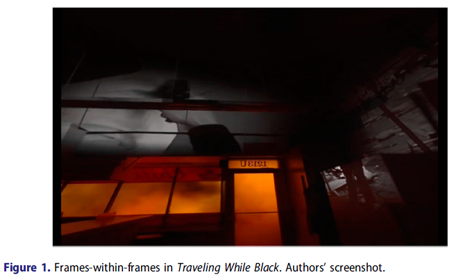

Ceuterick and Ingraham write that Traveling While Black sets the scene by beginning in a darkened space with black and white footage. Parts of the diner are superimposed over black and white images. They argue that this serves to “visually establish a continuity between the racism of the past and that of the present.” Viewers of Traveling While Black are immersed in the experience, but still remain somewhat separate from the film’s characters. For example, Ceuterick and Ingraham write that through the virtual diner, “we are given a concrete place in the virtual world: characters look at us, we are given a seat… and objects indicate our presence (e.g., via a virtual mug with hot coffee placed in front of us). On the other hand, we cannot act in the virtual world: we are left without a body, voice, or physical appearance.”

The film’s VR experience is also evocative of the lack of freedom that people have within racist systems. Ceuterick and Ingraham argue that the narrative of Traveling While Black demonstrates that “for some bodies, a freedom to travel does not mean a freedom from prejudice, imperilment, and fear.” For the viewers of Traveling While Black, this lack of freedom translates metaphorically to an inability to move. Viewers may look around the virtual diner, but they are unable to get up from their seat.

In the climax of Traveling While Black, Samaria Rice describes the murder of her son, Tamir Rice. In 2014, a police officer killed 12-year-old Tamir Rice when they saw him playing with a toy gun. Ceuterick and Ingraham argue that this narrative demonstrates to viewers the perils that Black Americans face from police violence and systemic racism. The film reminds viewers that these issues remain ongoing even in the face of progress since the 1960s’ civil rights movement.

Furthermore, Ceuterick and Ingraham argue that the climax of Traveling While Black immerses viewers not in the tragedy itself but in the representation of it through Samaria Rice’s testimony and security camera footage of Tamir Rice’s murder. The viewer becomes a participant in a room full of people listening to Samaria Rice. Viewers are not only invited to empathize with Samaria’s story, but also to witness and participate in an act of collective empathy. Ceuterick and Ingraham argue that the viewer is part of the scene because the characters look at the viewer, the viewer has a seat, and other elements indicate a physical presence in the diner. Yet, viewers still remain somewhat distant from the scene in the diner; they cannot fully interact with the virtual world because they don’t have a body or voice. The feeling of being in the diner allows the viewer to connect with the film’s subjects, yet the distance ensures that the film is not about the viewers and their feelings and that the focus remains on the experience of the subjects themselves.

Conclusion

Ceuterick and Ingraham conclude that VR has the potential to immerse viewers within a story, as both characters in it and witnesses to it. They write, “As we have explored through [Traveling While Black], it is the collective mediation of an event that situates us on the same plane as others in the virtual world, and it is by witnessing empathy that we may affectively cultivate our own.”